Service-to-service authorization: A guide to non-user principals

If a human had to provide an okay every time software applications or services needed to interact with one another the digital economy would no doubt grind to a halt. Service-to-service authorization is how such negative outcomes are avoided. Service-to-service authorization - also referred to as “machine-to-machine authorization” - enables two distinct software services or applications to grant permission or access rights to each other instantly, without the need for human involvement.

One of the common ways of tackling how systems made by different teams should interact with each other is to have each team build separate services that communicate with each other through APIs. It allows each team to develop and deploy their services autonomously.

When many teams’ services communicate through APIs, addressing the security, authentication, and authorization for your system changes. For example, in a monolithic application, all authentication would be handled by one codebase. Even with a handful of distributed services, crosscutting concerns, like logging, monitoring, rate limiting, and authorization, are generally all tied to a particular identity (usually a user).

However, in distributed systems using microservices, you can’t always rely on having access to the identity who’s making the public HTTP request. Background processing and downstream microservice requests are a couple of examples where you may not have access to that original identity.

So where does authentication happen now? Do all your services perform authentication or only the public-facing service? What about services between teams? What about when you don’t have access to the original identity which created the HTTP request? How do you know what any particular service is permitted to do? What if service A should have more access to your API than service B?

This is where authentication and authorization techniques around service-to-service communication can help. By assigning an identity to different services (non-user principals / non-human identities), you can retain the ability to perform rate limiting, monitoring, logging, authorization, and so forth for those specific services.

In this article, you will learn about non-user principals: what they are, when you may need them, and how they can help tame authentication and authorization in complex distributed systems.

What are non-user principals

Non-user principals are identities that you tie to objects, like servers and microservices. Why would you want to do that, you might ask?

There are times when you need to distinguish between the user’s identity, which is usually tied to authentication at the public edge of your application, and the identity of the calling service. Sometimes, you need to know who the users are (identity), for example, if you want to include their email address and name in an email. Other times, you need to know whether they are allowed to trigger an email to be sent (authorization).

However, there are cases when it makes sense to give specific services an identity that can be used in determining identity information and authorization. Doing this ties the non-user principals of the requesting service to rate limits, monitoring, messaging events, authorization, and logging.

Using non-user principals can benefit your distributed systems in various ways:

- Making sure the specific service is allowed to perform the action it is requesting gives you more coarse-grained authorization. In companies with many teams, this extra layer helps keep things secure and can be used as a specific security control as part of security compliance programs, like System and Organization Controls (SOC) or International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

- Rate limiting against non-user principals instead of public users is more coarse-grained and can help protect critical services from being overloaded with traffic coming from multiple teams and services.

- Monitoring against a non-user principal can expose which services are making too many calls or are being too “chatty.”

- Reusing the same authorization implementation for users and services can be done. You potentially don’t need to change your authorization logic and can reuse what currently exists for users.

When you might need non-user principals

Here are a few scenarios where using a non-user principal might make sense for you.

Protection of critical downstream services

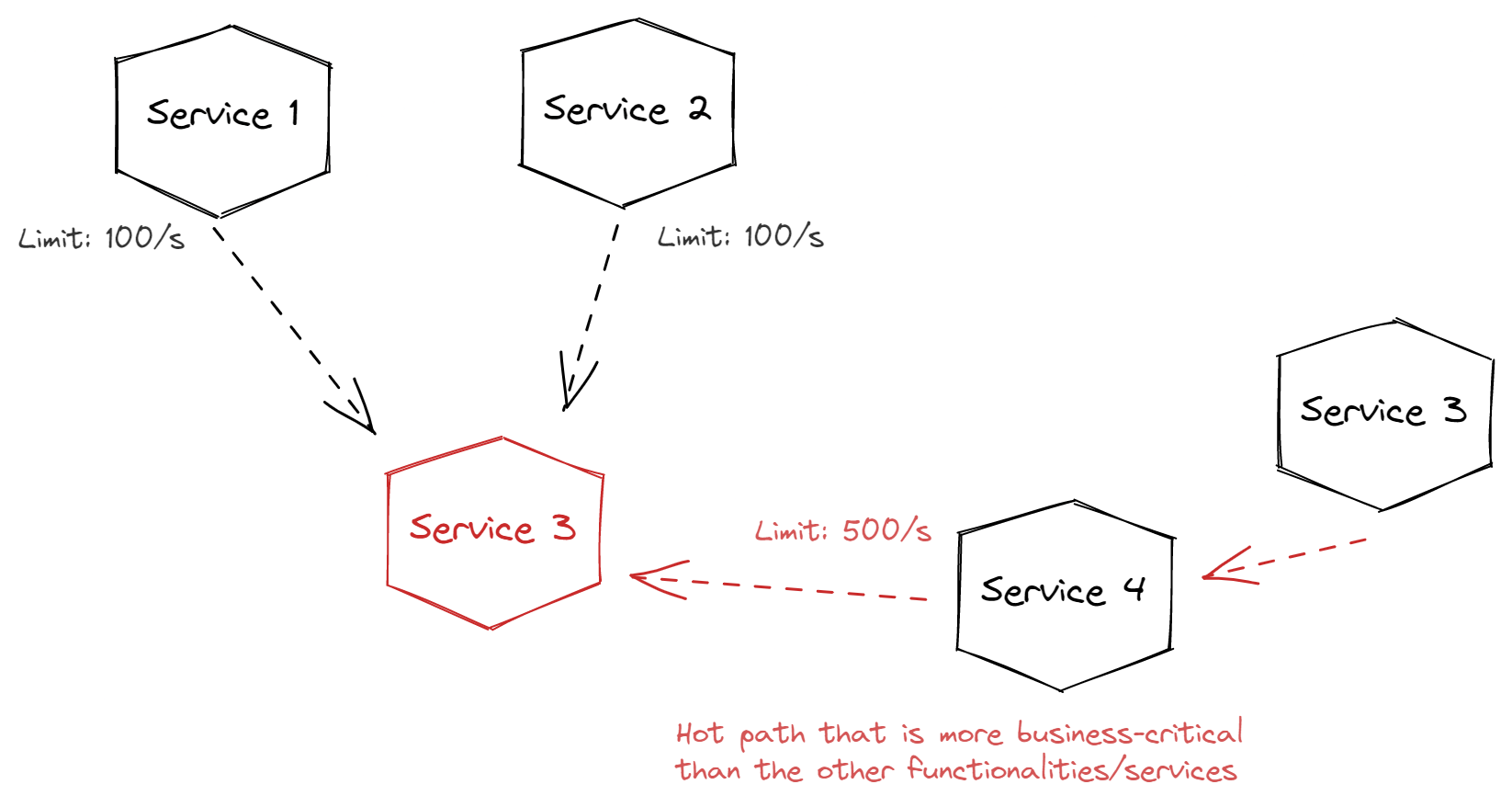

Using only the user principal to make requests to critical downstream services may introduce issues around the responding service having too much traffic.

For example, if a large number of users all try to issue the same function against your system, a downstream service that serves all those requests may begin to fail due to overloading. Since all the service has access to are individual users, it will then rate limit by each user or tenant.

If you give an identity to the services that call out to that downstream service, it can choose to give preference (that is, higher rate limits or more throughput) to the more important services. Instead of only limiting individual users, you can ensure that more important services have higher limits, too.

Background processing services

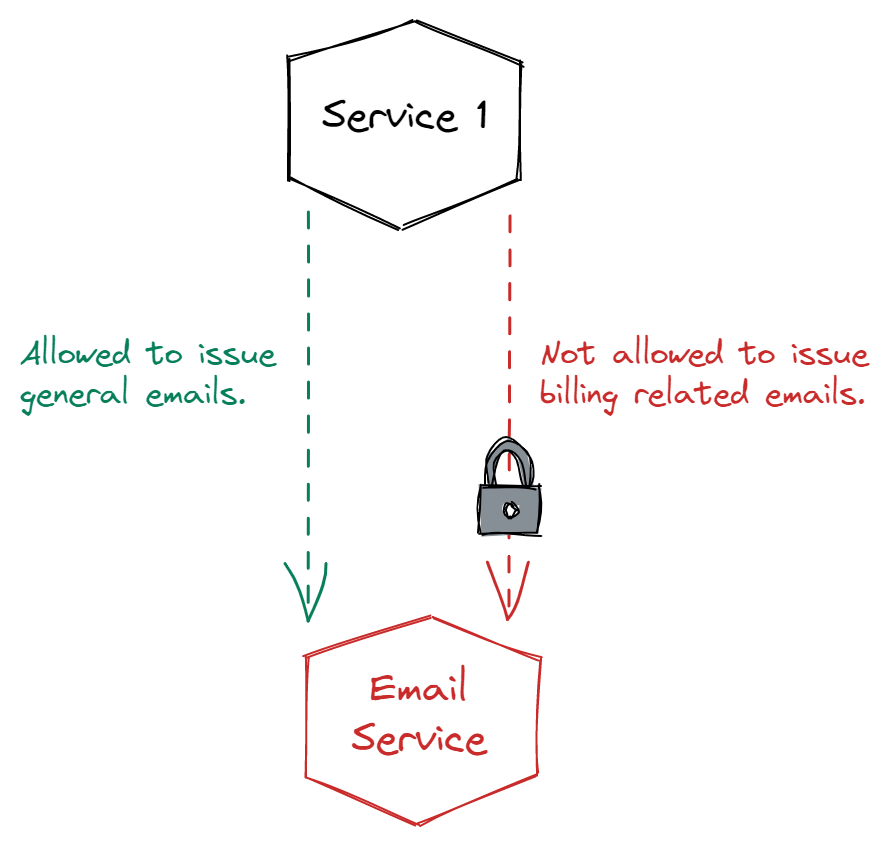

Many background applications and programs on your computer require certain permissions. Some background processes might need administrator privileges, while others can get away with limited privileges.

The same is true with microservices—some need higher privileges than others. A microservice that’s responsible for triggering generic emails to customers might not be allowed to trigger emails related to billing. Using non-user principals allows you to implement this type of security control.

Integration with APIs owned by other companies

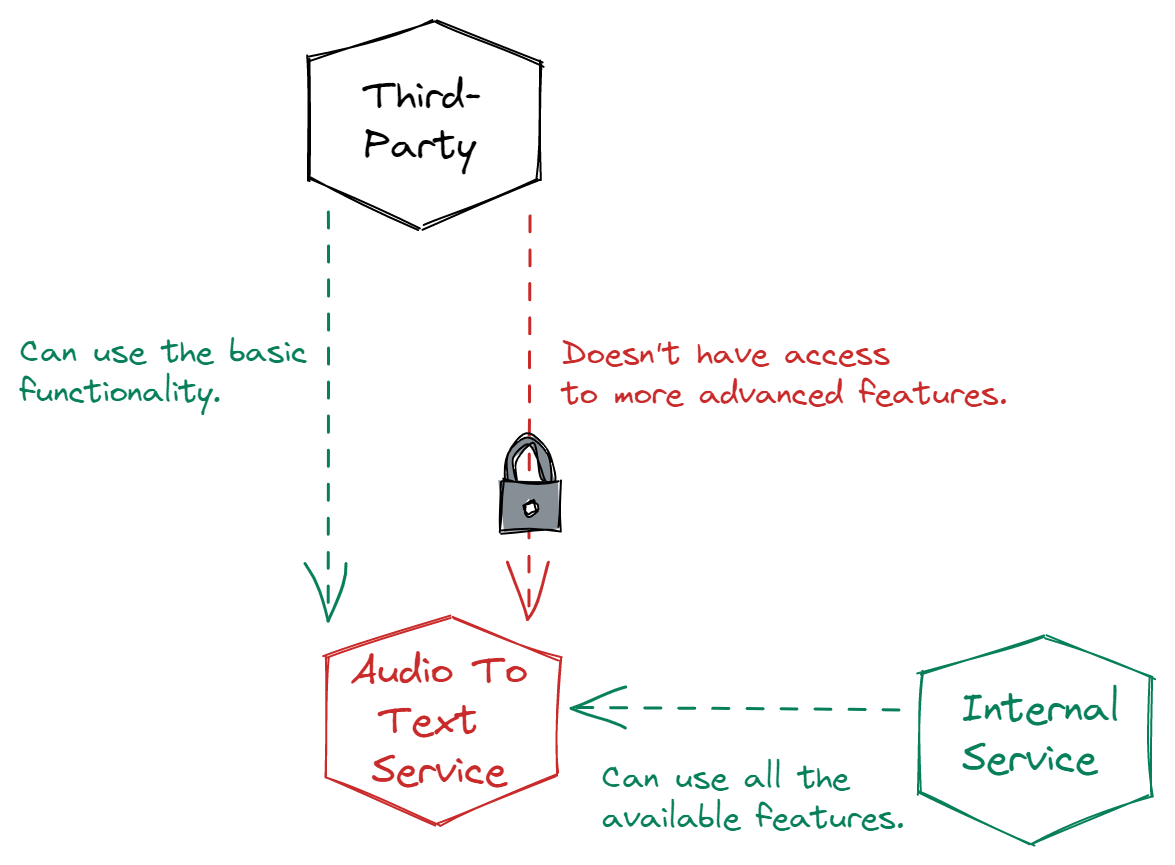

Let’s say you have a service that takes audio recordings and turns them into a text transcript. A third-party API wants to integrate with this service so it can use this functionality, too. But there’s no user identity since the third-party service itself is the identity.

In this case, the other service needs an identity created for it with permissions tied to its identity. It allows you to rate limit, monitor, and do other things against this third-party integration separate from your application’s users and microservices or APIs using this audio-to-text service.

How to build service-to-service authorization

Now you’re wondering,How can I implement this in the real world? Non-user principals are very similar to user principals. However, your implementation of how identities are created and used has to be flexible enough to be used by multiple microservices and potentially external services.

Authentication with microservices

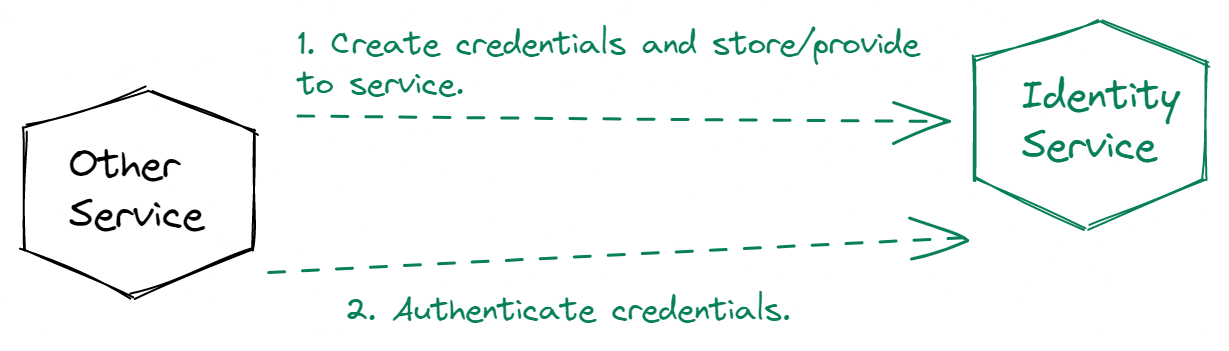

One of the common ways to do authentication in distributed systems is to have a dedicated authentication service. Often, this service is asked to authenticate a user principal by an API gateway so that further downstream services won’t have to reauthenticate the user.

In this design, the identity/authentication service can be an in-house service or a third-party authentication service, like Okta, OneLogin, and Auth0. The mechanism for issuing authentication could be JSON Web Token (JWT), long-lived API keys, or OAuth.

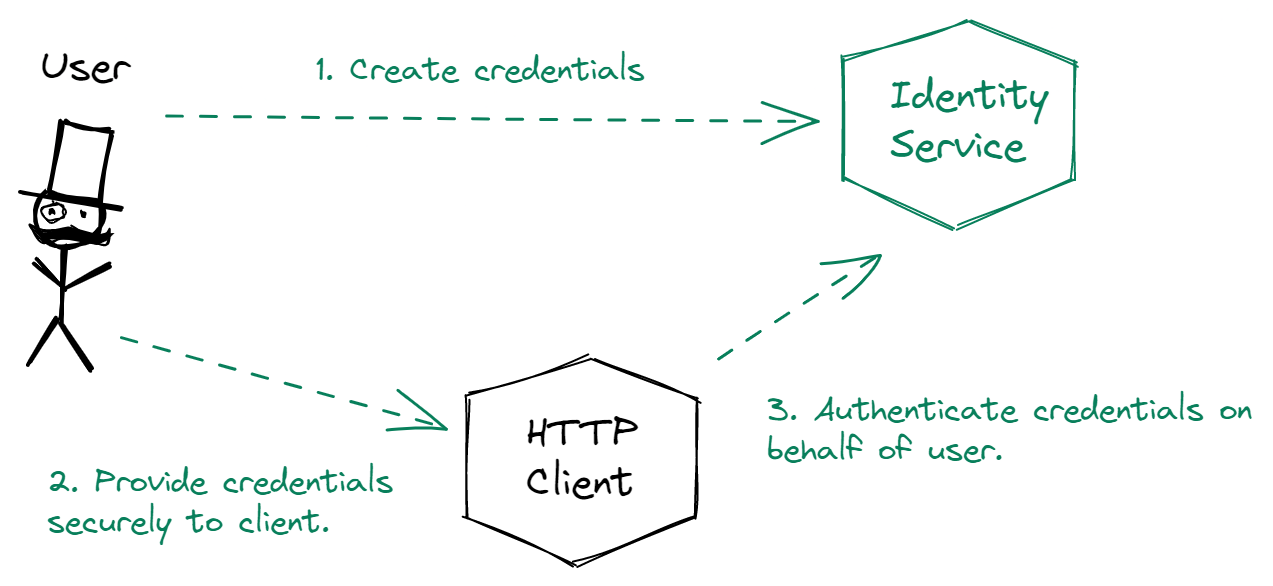

Here is the general flow for user authentication:

Notice that, usually, some HTTP clients (like an API or application) act on behalf of the user. Because of this, a few extra steps are usually needed to authenticate and get access to something like a short-lived token.

For non-user principals, the service is the identity. It also_is_ the HTTP client. It means that the service isn’t acting_on behalf_ of someone else, but it is the principal. Because of this, it can make sense for non-user principals to use a long-lived token of some kind (just like some of the Slack access tokens and Stripe restricted API tokens). Even if a short-lived token is preferred, OAuth has a special grant type for server-to-service communication.

Authorization with microservices and Cerbos

Where authentication is a matter of determining if the identity is who they really say they are, authorization is all about what that identity is allowed to do.

For example, Stripe can create API keys that restrict which APIs and features those specific keys are allowed to use. This is one way to configure what a specific user’s client is allowed to do.

However, when authorization needs to be managed in your own distributed applications, it’s not so simple:

- Should each microservice store authorization information for every user who can use that service?

- If so, should any of those services supply a UI for developers to generate, remove, and edit permissions for specific identities?

- How coarse or fine-grained should permissions be?

Especially in distributed systems, authorization can get hairy pretty fast. With authorization, many times, you aren’t simply checking if a specific user has access to certain actions within a system, but you are also checking many factors like the following:

- Type of user in question

- Department, team, or organization the user belongs to

- Custom exceptions applied to specific users or teams

- Other kinds of special flags

For the same reasons that many modern applications use third-party services to handle authentication, using a third-party service like Cerbos to handle authorization can help you build your system faster and make it more maintainable. Your authorization policies are stored as code so they can be kept in source control. Cerbos can also do things like compile and run tests against policies to make sure they work as expected.

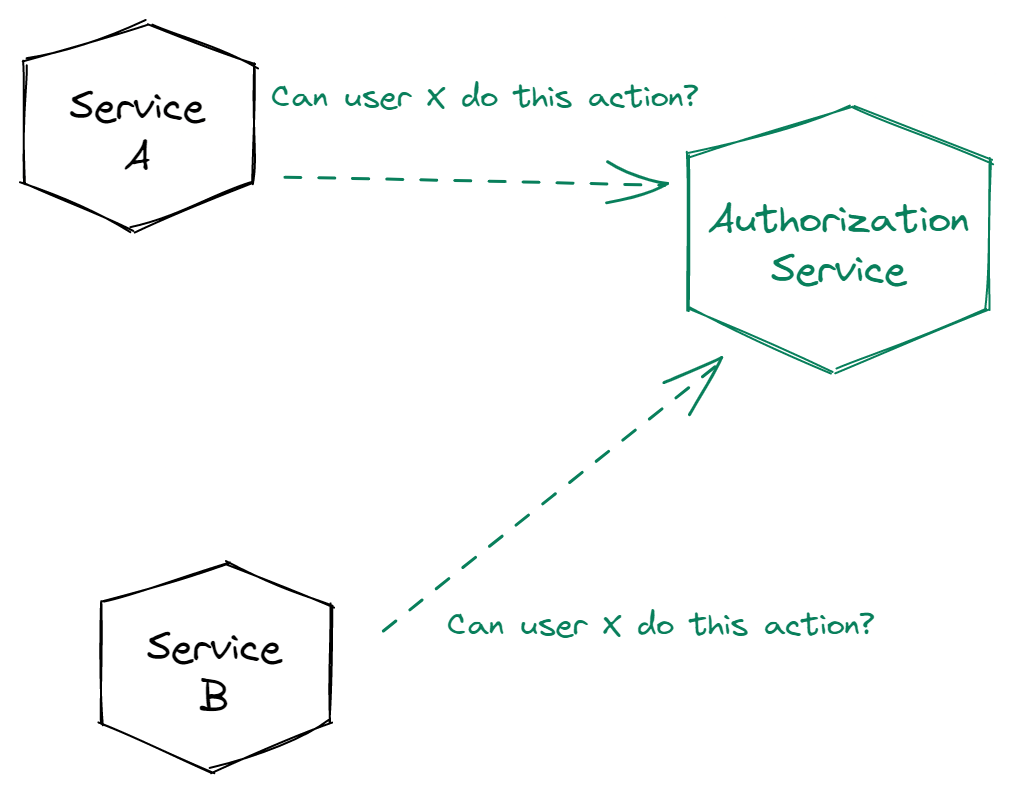

Generally, the implementation of authorization with Cerbos in a microservice environment is similar to authentication, except that each service needs to communicate with the authorization server themselves:

In terms of non-user principals, they behave very much the same as users. You can create policies that are specific to either a broad type of non-user principal, like internal services, or create specific policies per microservice.

Cerbos also supports many other deployment implementations, like being deployed as a sidecar, as a systemd service, or even as an Amazon Lambda service. In all these patterns, even if you deploy multiple instances of Cerbos, they will all be using the same policy repository. For example, deploying Cerbos as a sidecar means that each service will be able to issue HTTP requests to Cerbos within its physical network so that each request is very performant.

Conclusion

In this article, you’ve learned what non-user principals are and how they work. Whenever you’re faced with many services that need to interact with each other, it might make sense to give each service its own identity. This can help address crosscutting concerns, like rate limiting, monitoring, and logging, in the context of the service rather than the user who issued the original HTTP request. And as you learned, there are times when you may not have access to a user principal at all.

FAQ

Book a free Policy Workshop to discuss your requirements and get your first policy written by the Cerbos team

Recommended content

Mapping business requirements to authorization policy

eBook: Zero Trust for AI, securing MCP servers

Experiment, learn, and prototype with Cerbos Playground

eBook: How to adopt externalized authorization

Framework for evaluating authorization providers and solutions

Staying compliant – What you need to know

Subscribe to our newsletter

Join thousands of developers | Features and updates | 1x per month | No spam, just goodies.

Authorization for AI systems

By industry

By business requirement

Useful links

What is Cerbos?

Cerbos is an end-to-end enterprise authorization software for Zero Trust environments and AI-powered systems. It enforces fine-grained, contextual, and continuous authorization across apps, APIs, AI agents, MCP servers, services, and workloads.

Cerbos consists of an open-source Policy Decision Point, Enforcement Point integrations, and a centrally managed Policy Administration Plane (Cerbos Hub) that coordinates unified policy-based authorization across your architecture. Enforce least privilege & maintain full visibility into access decisions with Cerbos authorization.