How to implement scalable multitenant authorization

Building authorization for a software-as-a-service application often starts simple. With one customer or a handful of users, a basic role based access control model might suffice. But as soon as you add that second customer - or the hundredth, or thousandth - things get complicated.

Hardcoding permission checks throughout your code becomes a nightmare to maintain. In a multitenant architecture, where many customers share the same application, scaling authorization logic presents unique challenges.

In this post, we’ll explore those challenges and how dynamic, tenant-aware authorization models can overcome the limitations of static RBAC. We'll cover common multitenancy patterns, the dreaded "role explosion" problem with traditional RBAC, and how to shift to tenant-aware roles and attribute based access control. We'll also discuss best practices like decoupling authorization logic from your application, externalizing decisions to a policy engine, and treating policy as code.

Along the way, we will share insights from a recent demo video, which you can watch above, to illustrate these concepts in practice. And here is the application demo used in the recording.

The goal is to provide a clear blueprint for scaling authorization in multitenant SaaS systems. We hope you find this overview helpful and actionable.

If you're interested in an even deeper dive, we have a comprehensive 50+ page ebook: One size does not fit all: A guide to multitenant authorization. It walks through how leading SaaS companies implement dynamic multitenant authorization that scales without role explosion.

What makes multitenancy complex for authorization?

Multitenancy is fundamentally about multiple users or customer organizations sharing the same application infrastructure, with logical isolation between tenants. A useful analogy is to think of a multitenant system like an apartment building. The building has shared utilities and common areas (the shared application resources), but each apartment unit represents a tenant's isolated space.

Different people have different access rights: the building owner or manager might have a master key to every unit, while a tenant only has keys to their own apartment. Guests or maintenance workers get limited access. In software terms, we need to enforce that kind of isolation and varying access levels through our authorization logic.

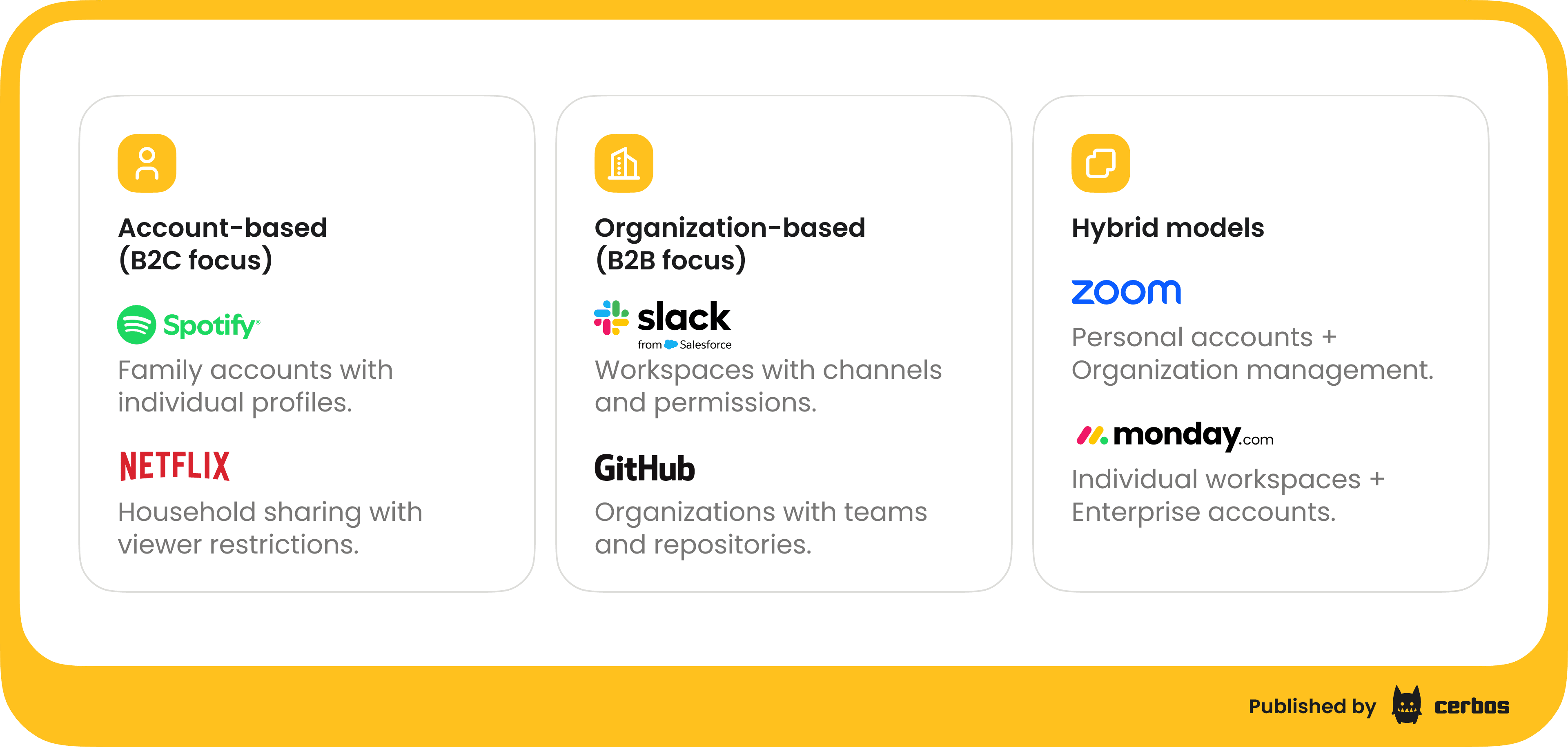

In a software context, multitenancy comes in a few flavors, and each presents its own authorization considerations.

B2C account-based multitenancy. In business-to-consumer scenarios, a single account might contain sub-profiles or members. For example, Spotify allows family accounts where one subscription has multiple user profiles under it. Each user in the family might have certain restrictions, e.g. parents versus children, within that shared account. Netflix has a similar household model: you share an account but can have individual user profiles with different permissions - think of parental controls on a kids' profile. Here, the "tenant" is the family account or household, and the app must enforce that a child profile can't view content outside its allowed set, even though it's under the same family subscription.

B2B organization-based multitenancy. In business-to-business SaaS, the tenant is often an organization or workspace. Applications like Slack illustrate this well. Slack has organizations (workspaces) that contain users, channels, messages, etc. If Bob is a member of Company A's Slack workspace, the system should ensure he cannot access Company B's workspace data, and vice versa - even if Bob happens to have an account on both. Within a Slack workspace, roles like Workspace Admin, Channel Owner, Guest, etc. determine what a user can do. Another example is GitHub Organizations: a user might belong to multiple orgs and teams, each with different repository access permissions. The authorization system must evaluate a user's actions in the context of the specific organization they are operating in.

Hybrid models. Some applications mix individual and organization contexts. Zoom, for instance, allows personal accounts - you can sign up as an individual, and organization accounts for businesses or teams. A user might have their own personal Zoom account and be a member of a company's Zoom tenant with a different set of permissions and features. Another example is monday.com, where you have personal workspaces but also enterprise accounts that aggregate multiple users and teams. In hybrid cases, the authorization logic must handle both individual-scoped permissions and org-scoped permissions, sometimes simultaneously.

The complexity arises because in a multitenant app, every action a user takes is contextual. It should be evaluated in the context of which tenant's data or resources the user is trying to access. Simply knowing that Alice is an "Editor" or "Admin" in a general sense isn’t enough; we need to know Admin of what? Which organization or account does that role apply to? As we'll see, failing to incorporate tenant context leads to some serious problems.

The limits of static RBAC in a multitenant world

Most of us start with a straightforward role based access control model. You define a few global roles like Admin, Editor, Viewer, etc., assign those roles to users, and sprinkle checks in your code like “if user.role == 'Admin' allow this action.” This works fine when your app has a single tenant or everyone is under one roof. But in a multitenant scenario, traditional RBAC shows its age very quickly.

The crux of the issue is that global roles are too coarse-grained and inflexible for multitenancy. An "Editor" role might have broad meaning in your app, but in reality, a user might be an Editor in the context of Tenant A and just a Viewer in Tenant B. If you only have one global definition of "Editor," you can't capture that difference. To compensate, teams often do the wrong thing: they create tenant-specific roles for each case. For example, you might define roles like Editor_TenantA, Editor_TenantB, Editor_TenantC, and so on, to try to differentiate permissions per tenant. This is the dreaded role explosion anti-pattern.

Role explosion is what happens when you proliferate roles to cover every combination of tenant and permission nuance. I've seen systems with more roles than actual users! Imagine a role that only one person ever has - it happens more often than you'd think. This over-encoding of roles leads to a few major headaches:

| Issue | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Management nightmare | The sheer number of roles becomes unmanageable. Every new customer or special case seems to require yet another role variant. You end up maintaining hundreds or thousands of roles and no one on the team truly understands what all of them do. Assigning roles to users or auditing permissions turns into a confusing, error-prone process. |

| Brittle, hard-coded logic | These tenant-specific roles often seep into authorization checks throughout your code. It's not just if role == "Editor" anymore, but if role == "Editor_TenantA" or role == "Admin_TenantA", etc., scattered in various services. The logic gets tangled and hard to update when requirements change (more on that later). |

| Security and compliance risks | Role explosion can become a compliance nightmare. It's easy to make mistakes when a user has a long list of roles. If roles are mis-assigned or not revoked properly, a user might retain privileges they shouldn't have. Also, authentication tokens (like JWTs) might start carrying dozens of role claims to cover all of a user's tenant-specific roles, which is not only inefficient but also harder to audit. |

| Static roles ignore context | Most importantly, the whole approach is flawed because it ignores context. A user like Sarah might be an Admin of the Marketing project but a Viewer in the Engineering project. She's not simply "Admin" or "Viewer" in general - it depends on where. A global role can't capture that nuance. As a result, if you try to enforce permissions with static roles alone, you'll either over-provision or under-provision access in each context. Sarah isn't an admin everywhere, so a global Admin role is too powerful; but she's also more than a mere Viewer in her own team context. Static roles break down because they lack this scope information. |

Let's put some numbers to the problem. Suppose your app defines 10 distinct roles for various purposes. If you have 1,000 customer tenants, a naive approach might end up with 10 × 1,000 = 10,000 role definitions to manage - one set of 10 roles per tenant. That's a huge policy management burden. Even worse, if a single user belongs to multiple tenants, they might accumulate a long list of role tokens that have to be interpreted in each context.

This "role proliferation" problem is a clear sign that traditional RBAC isn't scaling for your multitenant SaaS.

The good news is, there's a better way: make your authorization model tenant-aware and context-driven.

Tenant-aware roles. Same user, different tenants, different permissions

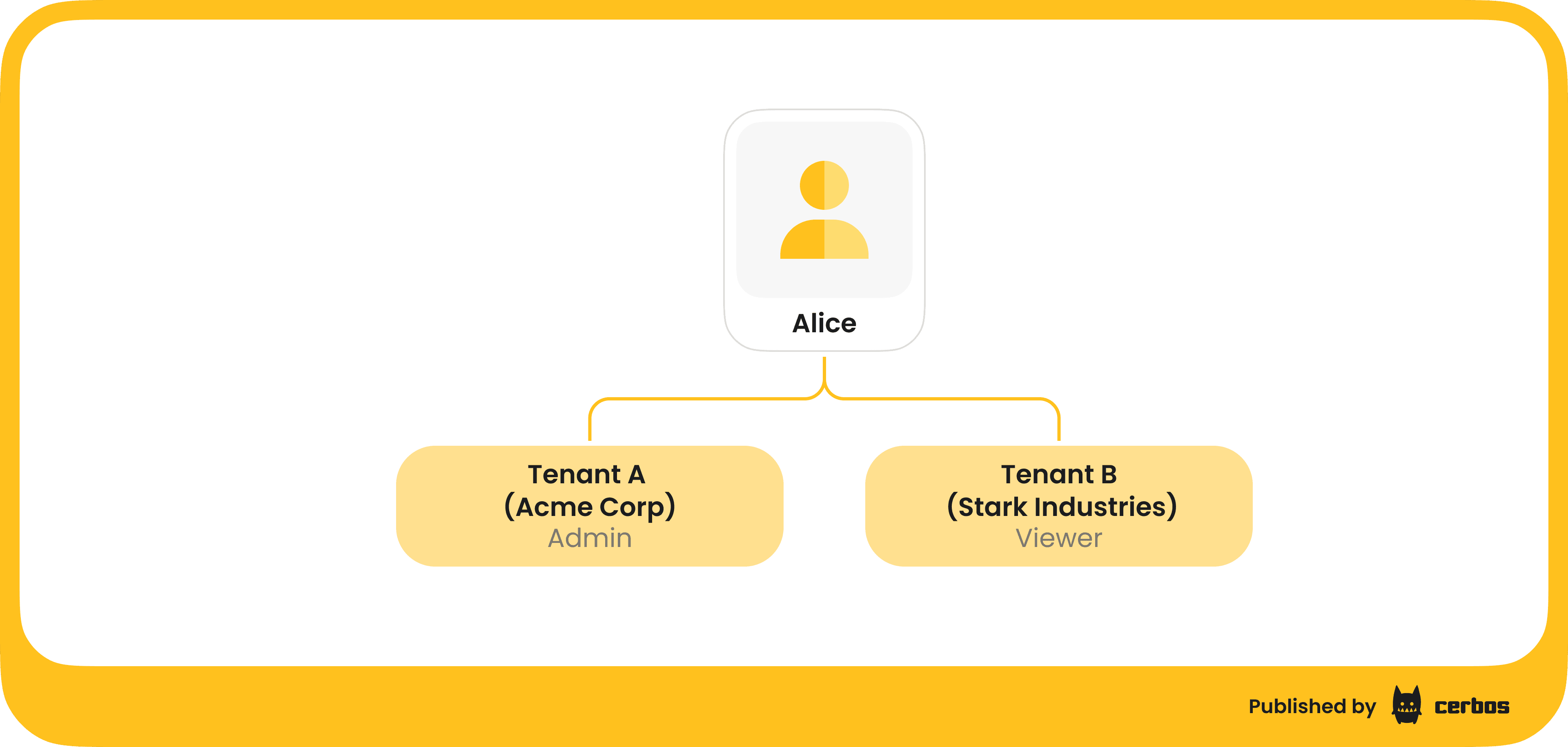

Instead of having one global role assignment per user, we shift to a tenant-aware authorization model. In a tenant-aware model, a user's permissions are always evaluated in the context of a specific tenant, or project, or workspace, rather than globally. In practice, this means a user can have different roles in different tenants, and the system checks the appropriate role based on which tenant's data is being accessed.

Concretely, imagine a user Alice who belongs to two organizations within a SaaS app: Acme Corp and Stark Industries.

Alice could be an Admin in the Acme tenant but just a Viewer in Stark Industries. When Alice tries to perform an action on an Acme Corp resource, the app should consider her Acme-specific role (Admin) and grant high-level privileges. But if she switches to Stark Industries data, the app should treat her as a Viewer with read-only rights. Same person, same account perhaps, but different effective permissions based on tenant context. This is exactly what we need for proper isolation: no more one-size-fits-all roles.

By making roles tenant-scoped, we avoid creating those bizarre cross-tenant role variants. You don't need "Editor_TenantA" and "Editor_TenantB" as separate roles anymore - you just have an Editor role that is understood within a given tenant. The user-role assignment is stored or encoded with a tenant identifier, for example, in your identity store or token, you might have claims like "role: Editor, tenant: Acme". The authorization logic then checks not just "does Alice have role Editor?" but also "for the tenant relevant to this request, is Alice an Editor in that tenant?"

This approach immediately reduces the combinatorial explosion of roles. It also aligns with how users expect the system to behave. If you ask Alice, "Are you an admin?", she'll likely respond, "Yes, for Acme Corp, but not in the other org." We want our system to enforce exactly that kind of contextual truth.

Making your RBAC model tenant-aware is the first big step toward scalable authorization in multi-customer apps. However, just introducing a tenant dimension to roles might not cover all use cases. Often, you also need more fine-grained control than roles alone can offer. This is where modern attribute based access control comes into play.

Going beyond roles with attribute based access control

Tenant-aware roles solve part of the problem by scoping permissions to the right context. But within a given tenant's context, you might have additional rules that determine access. Roles tend to be coarse-grained - either you're an Editor or you're not - whereas real-world requirements often depend on other factors (attributes) like resource ownership, status, or other properties. ABAC is an approach that allows you to use those attributes in your authorization decisions, not just roles.

With ABAC, you define policies that evaluate attributes of the principal (subject), the resource they want to access, and the action they're trying to perform. For example, let's break down a scenario:

-

Principal (subject) attributes. Who is the user? What roles do they hold in the current tenant? Are they the owner of the resource in question? Are they in a certain department or region? Is their account a service account or a human user? These are all potential attributes.

-

Resource attributes. What is the user trying to access? It could be a specific record or document. Attributes here might include which tenant the resource belongs to, a resource type (e.g. "expense report" vs "admin settings"), a status or state (draft/published, open/closed), an owner or creator ID, a monetary amount, and so on.

-

Environment/action attributes. What action is being attempted (read, write, delete, approve, transfer, etc.) and under what conditions (time of day, location, device, etc.)? Environment attributes are less common in basic SaaS apps but very relevant in security-sensitive domains.

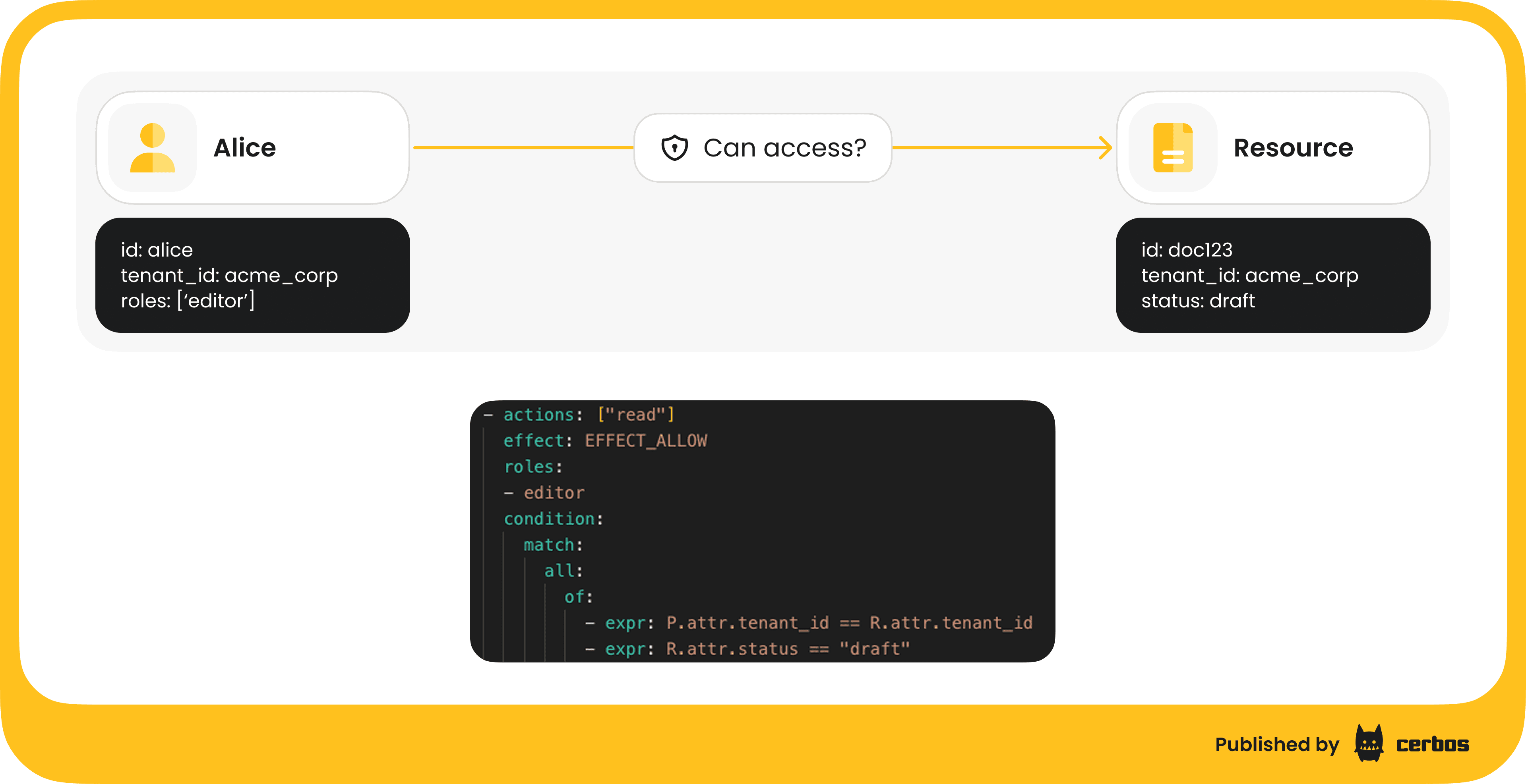

Using these attributes, you can craft fine-grained policies that decide whether to allow or deny a request. For instance, you might have a policy that says: "Users can only access resources if the resource’s tenant_id matches the user’s tenant and the user’s role in that tenant is appropriate for the action." This implements tenant isolation as a simple rule in policy rather than lots of repetitive code checks.

Another policy could be, "Expense reports can only be approved by users with the Manager role, and a manager cannot approve their own expense report." In that case, the policy would check attributes like resource.owner_id != user.id to enforce that separation of duties. You could even incorporate the expense amount as an attribute, allowing managers to approve up to a certain amount, and requiring higher-level approval beyond that - all without introducing new hardcoded roles.

To illustrate, consider Alice again. Suppose at Acme Corp she is trying to access a document with id: doc123 that has attributes tenant_id: acme_corp and status: draft.

A policy could state: allow access if user.role == "Editor" and resource.status == "draft" and resource.tenant_id == user.tenant_id. If Alice is an Editor for Acme and the document is a draft in Acme Corp, the policy evaluates to true - she can access. But if the document were in a different tenant, or not in draft status, the same Editor role wouldn’t be enough. In essence, role + conditions on attributes give much more granular control.

Cerbos, authorization solution for enterprise software and AI, is designed around this principle. It lets you write policies in code that combine role checks with attribute checks. Using Cerbos, teams can enforce not just multitenant isolation but also business-specific rules, all in one place (demo example a little further down).

ABAC isn’t a brand-new idea. The concepts have been around for decades. NIST has literature on it. But it's increasingly vital in modern apps. As systems grow more complex - think microservices, multi-tenant micro-frontends, or federated data, and as new use cases emerge, like machine-to-machine access with API tokens, or AI-driven actions - having fine-grained, context-aware authorization becomes a necessity. Roles alone won't cut it for those; attributes and policy rules fill the gap.

Decoupling authorization logic from application code

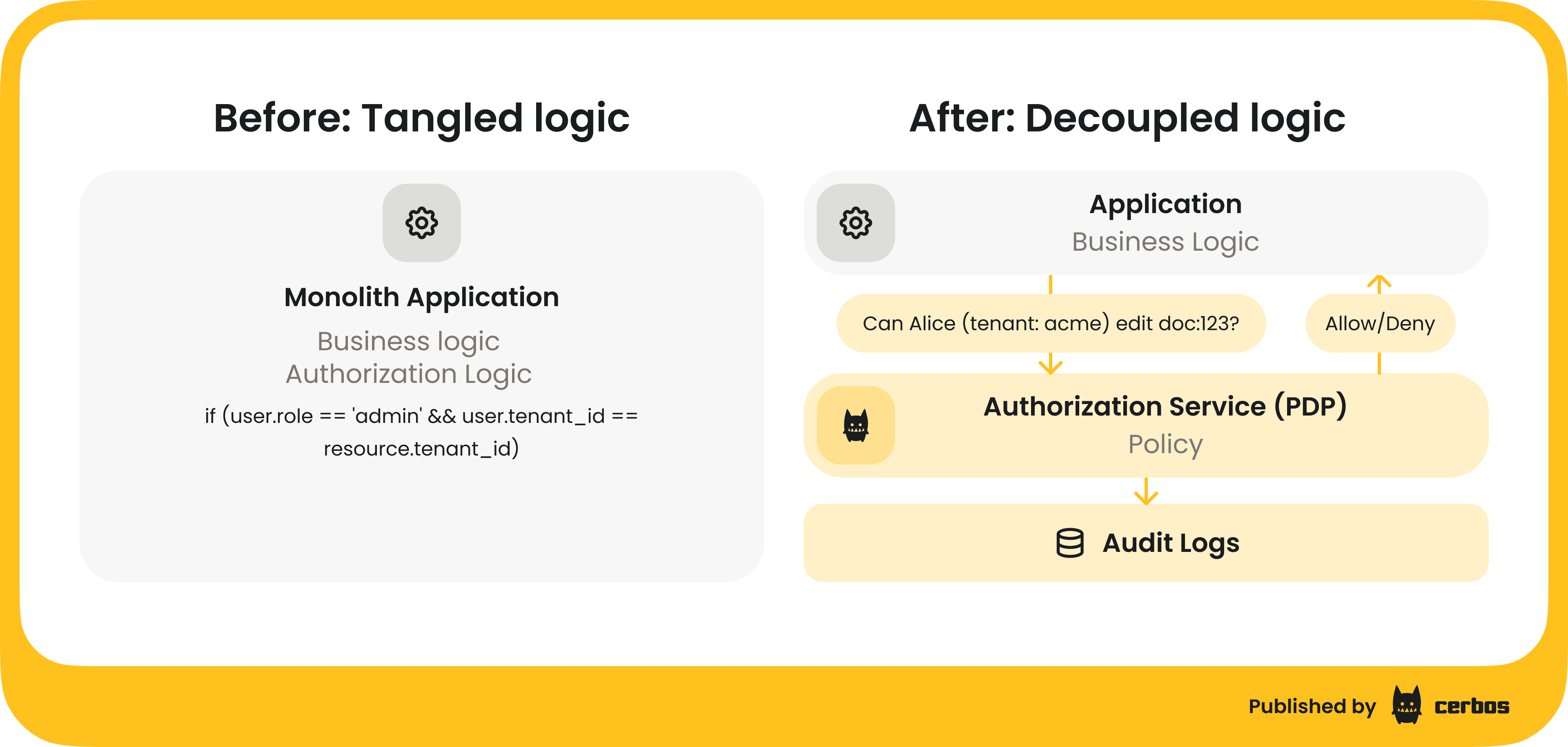

So far we've discussed modeling the rules of authorization: tenant-aware roles and ABAC policies. Now let's talk about architecture: how those rules are implemented and enforced in your software. One of the single most important architectural decisions in building scalable authorization is to decouple the authorization logic from your application business logic.

In many legacy or simplistic implementations, authorization checks are intertwined with the application code. Every time a sensitive operation occurs, you might see code like:

if user.role == "Admin" or (user.role == "Editor" and resource.owner_id == user.id):

# allow action

else:

# deny action

These if/else conditions, possibly checking tenant IDs or other attributes, get copy-pasted across your codebase. I've been guilty of this in the past, and I can tell you from experience, it becomes a brittle mess. It's hard to ensure every code path does the right checks, and when requirements change, you have to hunt down and update dozens of snippets of logic. Testing every permutation of roles and conditions means spinning up the whole app and running integration tests, because the logic is not isolated. If your application is a monolith, it's bad enough; if you have a microservices architecture with different services, in different languages, even, each might implement authorization slightly differently, leading to inconsistent behavior.

The better approach is to externalize authorization into a dedicated service or component often called a Policy Decision Point. In this model, your application - the Policy Enforcement Point, doesn't hardcode all the rules. Instead, whenever a user attempts an action, the app asks the PDP, "Is this allowed?" The PDP, which has all your policies (roles, tenant context, ABAC rules, etc.) loaded, evaluates the request and responds with a decision: Allow or Deny… sometimes with more nuance, but let's keep it simple.

Here's how it works step by step:

-

Application collects context. When a request comes in, your app or API gateway gathers the relevant info: Who is the user (subject)? What action are they trying? On what resource (which tenant, which object)? For example: Alice, attempting "EDIT" on doc:123 in tenant Acme. This context can be encoded in a query to the PDP.

-

Policy Decision Point evaluates. The PDP, which could be a library or a network service, receives that query and checks it against the authorization policies. It might retrieve additional attributes: some PDPs can call backends or have context loaded. Then it comes to a decision based on the policies: allow or deny, or sometimes "not applicable" if no rule matches, which you treat as deny.

-

Application enforces decision. The PDP returns a simple answer. Your application code then just has something like:

if decision == ALLOW: proceed; else: return 403 Forbidden. This is the only conditional logic the app itself contains with regard to authorization. Everything else is encapsulated in the policy and handled by the PDP. So your code is much cleaner: one call, one check.

The benefits of this architecture are huge. Firstly, no more scattered logic: policies live in one place, so when you need to update permissions, you do it in the PDP’s policy store, not in 20 microservices. Secondly, you can test policies in isolation. Since policies are data, or code, interpreted by the PDP, you can write unit tests for your authorization rules without running the whole app. This makes it safer to evolve your authorization model as requirements change. Thirdly, an external PDP can provide consistent decisions across an ecosystem. Every service that queries it will enforce the same rules, eliminating inconsistencies.

Another benefit is easier audit and compliance. A centralized authorization service can log all decisions: which policy was applied for which request, what the input was, and what the outcome was. If Alice was denied access to resource X at 12:00 GMT, you have a record of that. This audit trail is incredibly useful for debugging ("Why did Alice get a 403?") and for compliance reviews. It shows you have control over who can access what, and you can demonstrate enforcement of least privilege, separation of duties, etc.

Cerbos is an example of a PDP that you can integrate into your stack to achieve this decoupling. In fact, in our demo app, all authorization decisions were handled by Cerbos running as a service - our application frontend/backend just asked Cerbos for each action whether the user is allowed or not. By using a PDP like Cerbos, you externalize the heavy lifting: the app developers focus on core product features, and the authorization rules live in the policy service.

To sum up this best practice: Don't entangle authorization logic with business logic. Externalize it for cleanliness, flexibility, and maintainability. Not only will this save you from refactoring nightmares down the road, it also opens the door to advanced capabilities like dynamic policy updates, A/B testing of authorization rules, or even exposing controlled self-service permission management to your end customers, which we’ll discuss shortly.

Treating authorization policy as code

Decoupling authorization to a PDP gets you a clean architecture; now you can iterate on your authorization rules more independently. The next step is to manage those authorization rules (policies) with the same rigor as application code. This is often called "policy as code" and usually involves adopting a GitOps workflow for your authorization policies.

What does it mean to treat policy as code? It means you write your access rules in a declarative policy language or configuration, store them in a version control system like Git, and apply software engineering practices to them - versioning, code review, testing, continuous integration/deployment, etc..

Policies are no longer scattered if/else statements; they are first-class artifacts in your codebase, living alongside your application code or in a dedicated repository.

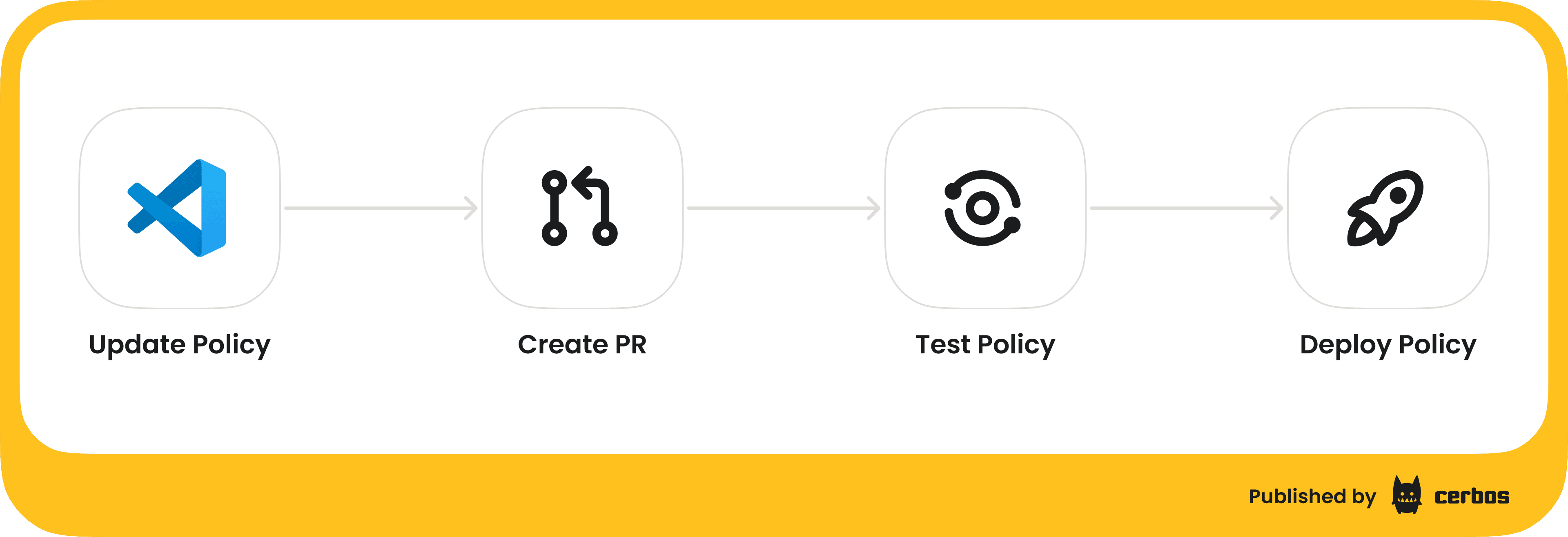

For example, with Cerbos you might write a policy file, in YAML or JSON, that defines the roles, attributes, and conditions for a certain resource type in your application. That file can be checked into Git. Let's outline a typical GitOps workflow for policy:

-

Write or update policy. A developer, or devops, or security engineer, makes changes to a policy definition: for instance, adding a new rule or modifying a role’s permissions for a tenant. This could be triggered by a new feature e.g., a new module in the app that needs permissions, or a change request: customer X needs a slightly custom role, etc..

-

Create pull request. The changes are submitted as a pull request in Git, just like any code change. This means the diff is visible, and team members can review the proposed changes. It's much easier to reason about "Allow managers to approve expenses up to $10k" when it's a few lines added to a policy file, rather than trying to review someone’s screenshot of code or, worse, no review at all.

-

Automated testing. As part of the CI pipeline for the repo, you run policy tests. Yes, you can and should test your authorization policies. For each policy, you can have a suite of test cases: "User with role X on resource with attributes Y should be allowed to do Z" and "should be denied to do W," etc. Cerbos, for instance, allows writing test scenarios that can be executed to verify the policy logic. In our demo, we had on the order of 800+ test cases covering various combinations of roles and conditions. These run quickly as pure functions. If a policy change accidentally violates an expected rule (maybe your update inadvertently allowed something that should be denied), the tests will catch it before anything is deployed.

-

Code review & approval. Team members review the PR. Maybe your security lead or another engineer signs off. This ensures a second pair of eyes on every authorization change: a crucial process when mistakes can have serious consequences. It's akin to reviewing code for a sensitive part of the system.

-

Merge and deploy. Once approved, the policy change is merged. A deployment pipeline then takes the updated policies and deploys them to the PDP service, or if the PDP is embedded, the new policy data is loaded. With Cerbos Hub in our demo, as soon as policies are updated and tests pass, the control plane compiles the policies and distributes them to all the policy decision points running in our environment. This happens automatically, so within seconds or minutes, all enforcement points are using the new rules.

-

Audit trail. Because policies are in Git, you have an immutable history of how your authorization logic has evolved. If something goes wrong or if an auditor asks "who allowed contractors to access repository X and when?", you can point to a specific PR/commit in the repo that made that change, including who reviewed and approved it.

The key benefits of treating policy as code include version history and the ability to rollback to a known-good state quickly, peer review for better quality, automated testing for confidence, and a clear audit trail of changes. It brings discipline and agility to authorization, which historically was often an afterthought or manually managed. Today, especially in enterprise scenarios, policy updates might be frequent and need to be done safely: a policy-as-code approach is the answer.

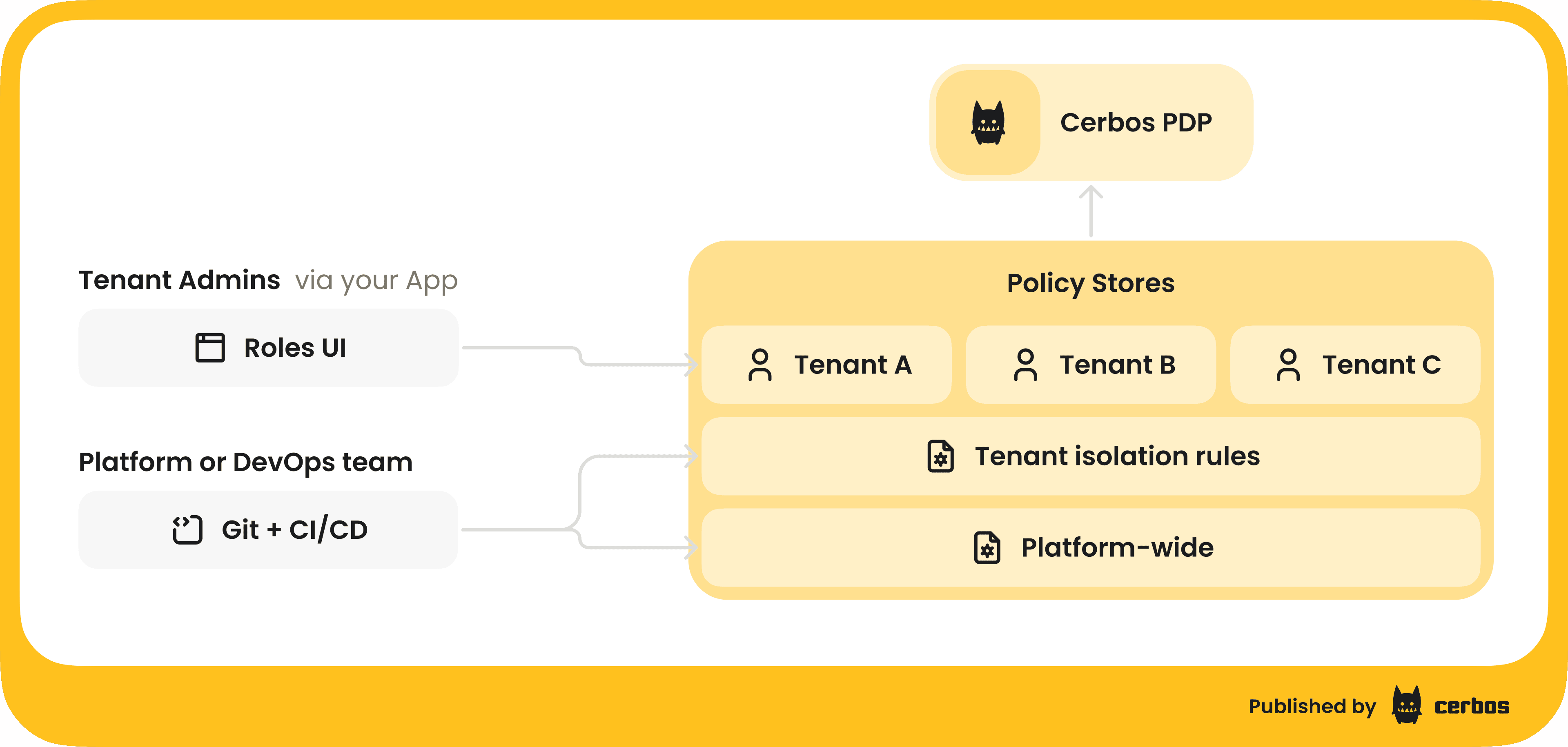

In the demo, we demonstrated this by using Cerbos in conjunction with a GitHub repository and CI pipeline. Our platform’s base authorization policies, the ones that apply to all tenants, defining overall system rules, were stored in GitHub. Every change triggered a build that ran all policy tests and then published the updated policies to Cerbos. This ensures that even as we empower tenants with some self-service (next topic), the underlying guardrails are rigorously managed and not subject to ad-hoc tweaks in production.

Balancing central control and tenant self-service

One question that often comes up is: if we externalize and strictly control our policies as code, how do we handle scenarios where customers (tenant admins) want to manage roles and permissions themselves? In B2B SaaS, it's common to allow an organization's admin to create custom roles or invite users and assign roles within their tenant. We want to enable that kind of self-service for convenience and scalability: you don't want to be on the hook for every permission change in every customer account. But we want to do that without sacrificing the consistency and security of our overall authorization model.

The solution is a layered approach: maintain central, platform-wide policies and allow tenant-scoped policies or configurations that can be managed dynamically. The central policies enforce things that should never be violated. For example, "a user can never access data from a tenant they don't belong to" might be a global rule. On top of that, you permit each tenant to have their own roles and fine-grained rules, but those are constrained to that tenant's scope and often to a subset of actions.

In our demo, we showed how Cerbos can handle this by treating tenant-specific role definitions as data. The SaaS platform provides a UI where a Tenant Admin can create a new role (say, “Auditor”) and specify what that role can do within their tenant. For example, the Auditor role might be allowed to view expense reports but only those in the North America region, and not perform any edits. The admin picks these rules via checkboxes or form inputs in the app UI. When they hit "Create Role," two things happen behind the scenes:

-

Identity update. The new role "Auditor" is created in the identity provider, in our case Keycloak, as mentioned in the webinar, so that users can be assigned to it.

-

Policy update. A tenant-scoped policy is generated, via API/SDK call to the authorization service, that encodes the permissions for the "Auditor" role just for that tenant. Essentially, the choices the admin made in the UI are translated into an ABAC policy specific to, say, Acme Corp's tenant space. This policy might say: if user.role == "Auditor" (and tenant == Acme) then allow read on expenses where region == "NA".

Because we set up our Cerbos deployment to watch for both global Git-managed policies, and dynamic tenant policies, the system picks up this new tenant policy immediately, runs it through the test pipeline, and deploys it to the PDP instances. Within moments, the new role is live. When a user with the "Auditor" role in Acme logs in, the token says they have role Auditor (in Acme tenant), and Cerbos now has rules for what "Auditor" means in Acme. That user will see exactly the limited set of data we intended, e.g., only North America expenses.

Meanwhile, tenant B, another customer, could define their own roles perhaps with different constraints, and it would generate separate policies scoped to tenant B. The platform’s core policies continue to enforce universal rules, like cross-tenant isolation and overall actions that are not allowed at all, so no matter what a tenant admin configures, they can’t break out of the sandbox. This approach gives central control to the platform provider (us) and flexibility to the tenant admins.

From an architectural perspective, achieving this requires that your PDP supports multi-tenant policy segregation and on-the-fly policy updates. Cerbos, for instance, allows scoping policies to a tenant identifier and has APIs to push dynamic policies at runtime. It also supports combining those with the version-controlled base policies in a seamless way, and running tests as policies are added to ensure nothing conflicts unexpectedly.

The result is a powerful setup: as the platform owner, you define the authorization blueprint: what can be done in the system and fundamental security invariants. And, you delegate to your customers the ability to do the fine-tuning for their organizations: create roles, assign users, set certain limits. You maintain an audit log of both the central and tenant-level changes. This balances security and flexibility, which is often a requirement for winning enterprise deals.

In the demo, we saw this in action with a fictitious expenses app. The Acme Corp admin created a custom Auditor role restricted to a region. We then logged in as a user with that role and verified that the user’s view was limited to just the allowed subset of data. Under the hood, Cerbos had combined the central rules, ensuring the user can't see another tenant's data, for example, with the new tenant-specific rules (limiting by region) to make each decision. And because this all ran through the policy engine, every decision was logged and could be audited later. The demo shows how dynamic authorization in a multitenant system can work smoothly.

Key takeaways for scalable multitenant authorization

Multitenancy introduces new challenges for authorization, but by adopting the right model and architecture, you can address them cleanly. Here are the key takeaways and best practices from our discussion:

| Go tenant-aware | Move away from rigid global roles and embrace context-driven access control. A user's permissions should depend on which tenant’s data they're acting on. This avoids one-size-fits-all roles and prevents role explosion. In short: the same user can be an Admin in one context and a Viewer in another, and your authorization model must reflect that. |

|---|---|

| Adopt attribute based access control (ABAC) | Don’t rely solely on roles. Incorporate attributes like tenant ID, resource ownership, status flags, etc., into your authorization decisions for fine-grained control. ABAC policies enable rules like "managers can approve only if the record is in their department and it's in draft state," capturing business logic that roles alone can’t express. |

| Decouple authorization logic from application code | Externalize your authorization checks to a dedicated service or library Policy Decision Point such as Cerbos. This clean separation makes your app code simpler (just ask "allow/deny?"), ensures consistency, and allows you to change authorization rules without touching application code. It also gives you an audit log of decisions out-of-the-box. |

| Treat policy as code | Manage your authorization policies with the same discipline as application code. Use version control, code reviews, and automated tests for your policies. This practice improves the quality of your permission rules and builds trust that you can evolve them safely. When done right, you'll have an auditable history of every change to your security model and the ability to roll back if something goes wrong. |

| Enable tenant self-service safely | Where appropriate, empower your tenants to manage roles and permissions within their own org. Do this on top of a robust platform policy foundation that enforces global invariants. The combination of central control and tenant-specific policies lets you scale administration and delight enterprise customers without relinquishing overall security. Design your system to handle dynamic policy updates per tenant in real time, with proper validation and isolation for each tenant’s rules. |

By implementing these practices, you can avoid the pitfalls of static RBAC in a multitenant environment. Instead of drowning in thousands of roles or brittle spaghetti code, you'll have a clear, maintainable authorization layer that scales as your customer base grows. Multitenancy doesn't have to mean multi-headed complexity in your access control logic.

In summary, dynamic authorization - combining tenant-aware roles and ABAC, enforced by an external policy engine - is the key to scalable, secure multitenant SaaS. It resolves the role explosion problem by making context a first-class citizen in your permission checks. It provides the flexibility to meet varied customer needs while maintaining strict isolation between tenants. And with a modern policy-as-code workflow, it gives you the agility to adapt and the confidence that you can prove compliance at any time.

If you're interested in seeing this in action or exploring how it might apply to your own applications, I encourage you to check out the full webinar recording here.

For an even deeper dive, check out our 50+ page ebook: One size does not fit all: A guide to multitenant authorization. It walks through how leading SaaS companies implement dynamic multitenant authorization that scales without role explosion

Or, reach out for a chat. We would be happy to help you define and manage tenant specific policies dynamically for every tenant, customer, or organizational unit.

FAQ

Book a free Policy Workshop to discuss your requirements and get your first policy written by the Cerbos team

Recommended content

Mapping business requirements to authorization policy

eBook: Zero Trust for AI, securing MCP servers

Experiment, learn, and prototype with Cerbos Playground

eBook: How to adopt externalized authorization

Framework for evaluating authorization providers and solutions

Staying compliant – What you need to know

Subscribe to our newsletter

Join thousands of developers | Features and updates | 1x per month | No spam, just goodies.

Authorization for AI systems

By industry

By business requirement

Useful links

What is Cerbos?

Cerbos is an end-to-end enterprise authorization software for Zero Trust environments and AI-powered systems. It enforces fine-grained, contextual, and continuous authorization across apps, APIs, AI agents, MCP servers, services, and workloads.

Cerbos consists of an open-source Policy Decision Point, Enforcement Point integrations, and a centrally managed Policy Administration Plane (Cerbos Hub) that coordinates unified policy-based authorization across your architecture. Enforce least privilege & maintain full visibility into access decisions with Cerbos authorization.