Zero Trust in cybersecurity - how it works

Cyber attacks are happening at an alarming rate, over 86% of organizations have experienced a successful cyber attack in recent years. The financial stakes are high too: the average data breach costs on the order of $4-5 million for companies.

In a talk at CyberWise Con, Cerbos co-founder and CPO, Alex Olivier, highlighted these sobering statistics and even recommended a book - This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends by Nicole Perlroth, which chronicles the global cyber arms race. Bottom line: today’s threat landscape is more sophisticated and dangerous than ever, and our security approaches need to keep pace.

Modern attacks exploit everything from expanded cloud footprints and remote work vulnerabilities to supply chain and AI-powered attacks. Yes, even ransomware call centers are being replaced by chatbots. With threats coming from all angles, it’s no longer enough to rely on a strong perimeter or a single line of defense. We have to assume that breaches will happen eventually and design our systems to mitigate damage. In cybersecurity, like in aviation safety, only a layered defense can stop isolated failures from cascading into a catastrophe.

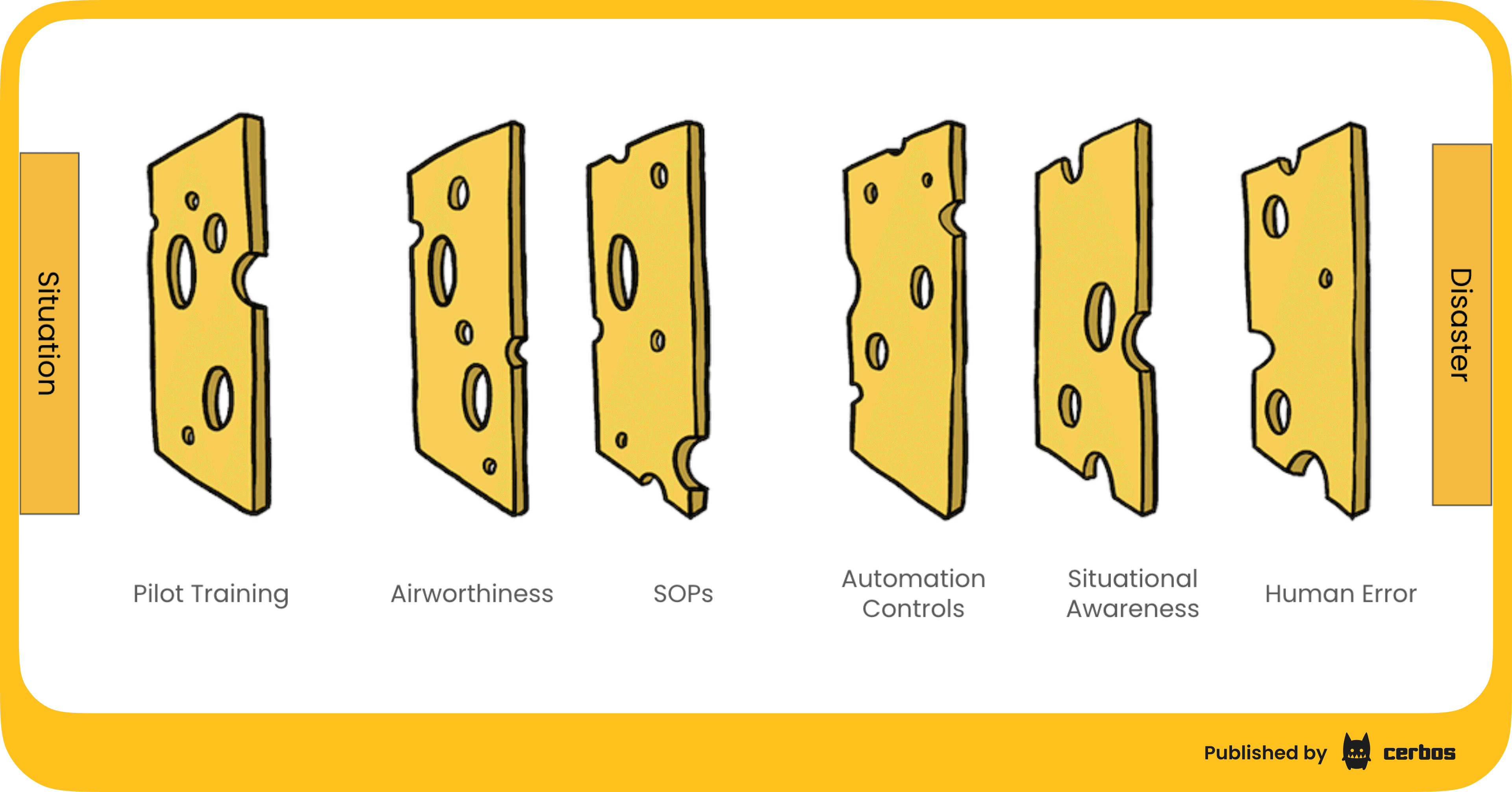

Learning Zero Trust from aviation. The Swiss Cheese model

Aviation has spent decades refining safety through rigorous processes and engineering, and a lot of these lessons translate well to cybersecurity. Alex introduced the audience to James Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model” of risk management. In this model, each layer of defense in a complex system is like a slice of Swiss cheese: it has holes (flaws or gaps), but multiple layers stacked together can cover each other’s holes. An accident or breach occurs only if the holes in all the layers happen to align perfectly, allowing a threat to slip through all defenses. The goal, of course, is to have enough independent layers that it becomes extremely unlikely for all of them to fail at once.

In aviation, these layers include things like pilot training, mechanical safety checks, standard operating procedures, and automated fail-safes. Alex gave an example of an aircraft flight control system using triple modular redundancy: three separate computers each get the same sensor data and “vote” on aircraft control decisions. Only if at least two computers agree will the system act. This consensus mechanism ensures that a single faulty sensor or computer won’t cause a crash - it’s a layer of cheese that catches one computer’s error with the redundancy of the others. The broader point is that no single safeguard is foolproof, but multiple safeguards dramatically reduce the odds of disaster.

A layered security approach

So how do we apply the Swiss Cheese model to software systems? The traditional perimeter-based security model assumed that if you kept the bad guys out of your network with firewalls, VPNs, etc., everything inside could be trusted. That approach doesn’t hold up well anymore. Modern environments are too fluid, and threats can originate from inside or easily breach a single barrier.

Instead, the industry is embracing Zero Trust principles: “never trust, always verify”, enforce least privilege, and assume breach as a starting point. In practice, this means implementing multiple layers of defense and verifying every action or request, not just the initial entry.

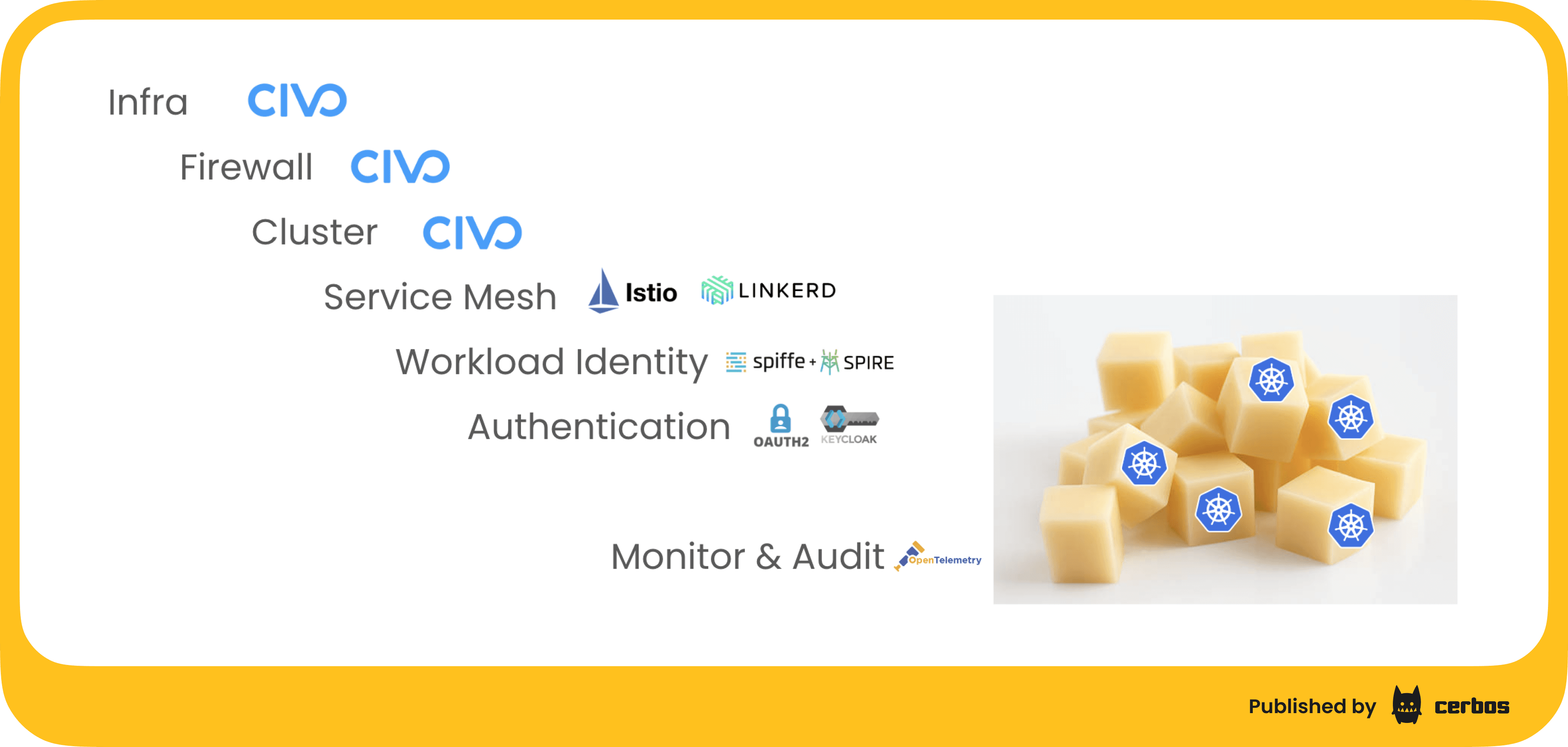

What do these layers look like in a modern cloud architecture, for example, a Kubernetes setup? You might start with your infrastructure and network controls: cloud providers and container platforms let you define firewalls and security groups at the perimeter. On top of that, you add network segmentation inside your environment, for instance, using a service mesh like Istio or Linkerd to enforce policies on which services can talk to each other. You’ll also encrypt data in transit (TLS everywhere) and at rest, so that even if someone intercepts traffic or steals a database, they can’t read sensitive information.

Next, you establish strong identity and access management. That means robust authentication for both users and services. Protocols like OAuth2/OIDC (with tools like Keycloak for single sign-on) ensure every user or API client is positively identified. Even machine workloads get identities: frameworks like SPIFFE/SPIRE can issue each service a cryptographic identity so that services authenticate to each other with certificates, eliminating blind trust in just being “inside” the network. All of this addresses the “verify explicitly” part of Zero Trust - every request is authenticated based on who or what is making it.

Another crucial layer is monitoring and audit logging. With distributed tracing and telemetry (using something like OpenTelemetry), plus centralized log collection and analytics, you gain visibility into what’s happening across all these layers. This helps detect anomalies and provides an audit trail if an incident does occur. It’s part of the “assume breach” mindset: continuously watch for signs of trouble and be ready to respond.

Stacking these measures gives a pretty solid defense in depth. However, as Alex pointed out in his talk, there’s one more layer of cheese that is often overlooked, and it’s a big one. After you authenticate a user or service, what are they allowed to do within your system? This is where authorization comes in, and it’s increasingly recognized as the critical missing piece of Zero Trust architectures.

The missing layer: Authorization

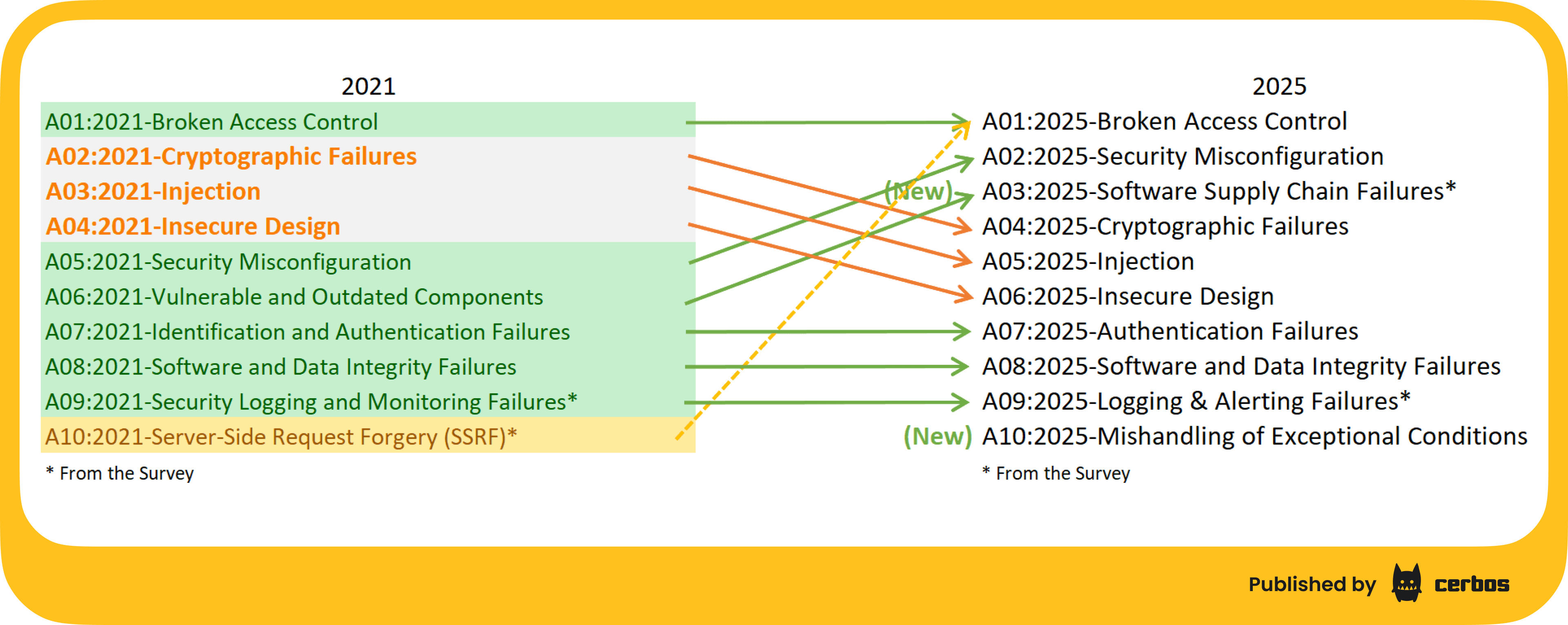

After jumping through all the hoops of network and identity security, a user or service may have a valid login token, but that doesn’t mean they should have free rein over your data or functions. Authorization is the process of checking what actions an authenticated entity is allowed to perform. And it turns out that broken authorization, a.k.a. broken access control, is a leading cause of security vulnerabilities.

In fact, “Broken Access Control” is the #1 most serious web application security risk in the OWASP Top 10 2021 edition, and in the 2025 edition. In plain terms, that means many breaches are not due to someone picking a lock to get in. They often happen because once inside, the attacker can move laterally or access things they shouldn’t, due to missing or flawed permission checks.

It’s important here to clarify terminology that often causes confusion. Authentication is proving who you are - for a user, this might be logging in with a password or SSO; for a service, it could be presenting a client certificate or API key. Authorization, on the other hand, is deciding what you are allowed to do. As Alex quipped, the HTTP header named “Authorization”, with a bearer token, is really carrying credentials to authenticate you. The actual authorization comes after, when the system checks your permissions. In a Zero Trust approach, authenticating a user or service is just the beginning; every subsequent action should be authorized based on policy. Never trust, always verify - on every request.

Why is authorization so often the weak link?

One reason is that it tends to get more complex as software and organizations grow. Let’s walk through a common evolution.

1. Basic roles (the early days). In a brand-new app, you might start with a simple role-based check. For example, your code might say, “If the user’s email ends with @mycompany.com, they are an admin, otherwise they’re a regular user.” This simplistic logic, essentially hard-coded roles, works initially - it’s easy to implement and understand.

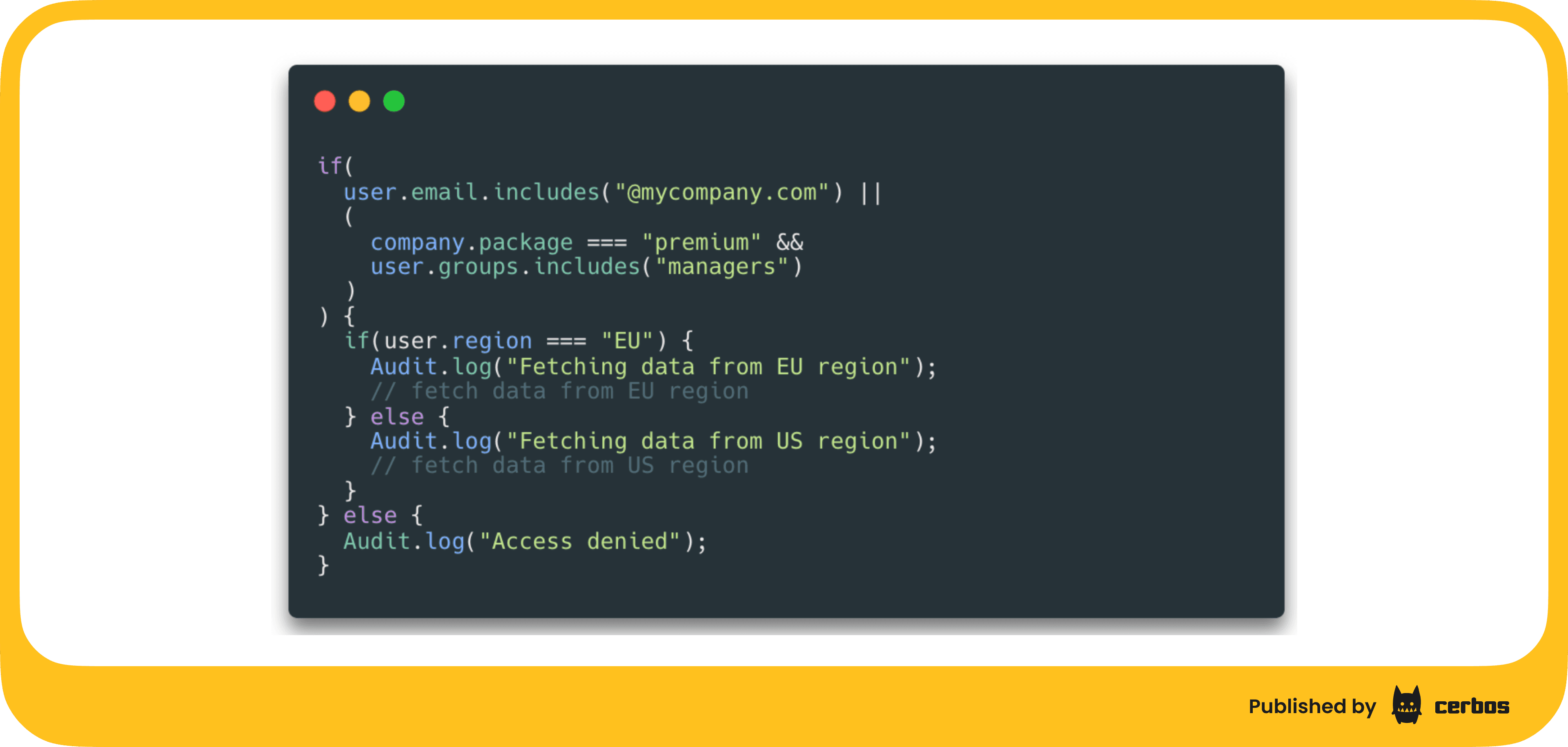

2. Feature gating and tiers. As the product grows, you add features and maybe subscription tiers. Now you need to restrict certain features to premium customers, or implement “entitlements.” The authorization logic starts getting more complicated: your code checks not just who the user is, but what plan they’re on, or what features their account has enabled. The once-simple if statements in your code multiply to handle these business rules.

3. Data residency and compliance. Fast forward, and perhaps you expand globally or face regulations like GDPR. You might need to ensure users from Region A can’t access data stored in Region B. This introduces another dimension to access control - the user’s region or legal jurisdiction, and your authorization checks must incorporate those rules. Alex shared a war story of when an EU-US data sharing agreement (Safe Harbor) was invalidated, forcing his team to rapidly segregate data by region and enforce those restrictions at runtime. Implementing those rules in code, across a large distributed system, was a nightmare.

4. Enterprise customers and hierarchies. As your product gains large enterprise customers, you encounter demands for more complex role hierarchies. A customer with 50,000 employees might say, “We need department managers to have access X, regional managers access Y, and only global admins can do Z.” Your simple roles of “admin” and “user” aren’t sufficient. You need to integrate with external identity providers or directories, like Active Directory or Okta groups, and suddenly your app must understand nested groups or attributes that represent organizational structure. The authorization logic in your codebase balloons in complexity to accommodate these requirements.

5. Audit and accountability. With bigger customers, especially in regulated industries, comes the need for auditing every access decision. It’s not enough to enforce the rules; you must also log who did what and when, and be able to prove it later. During compliance audits (ISO 27001, SOC 2, etc.), you may be asked to show logs of access control decisions. If your authorization logic is spread out in code, gathering comprehensive logs is tricky. You end up sprinkling logging calls alongside every permission check - assuming the checks themselves are consistently implemented in the first place.

6. Microservices and multiple applications. To top it off, modern architectures are often polyglot and microservice-oriented. Instead of one monolith where all access control logic lives in one place, you now have dozens of services. Some are written in Java, some in Python, some in JavaScript, etc. Each service might need to enforce certain authorization rules. Duplicating complex logic in each service, and in each language, is not only tedious - it’s a recipe for inconsistency. One service might forget a check or implement it incorrectly, reintroducing vulnerabilities you thought you had covered elsewhere.

It’s easy to see how authorization can become messy and error-prone over time. What started as a couple of if statements can evolve into a scattered web of conditional checks across many codebases, as the below example.

This is not only hard to manage and update, but also hard to audit. When an auditor asks, “Who has access to delete records, and what ensures they can’t delete someone else’s data?” - you want to answer confidently, not scramble through code trying to demonstrate the logic.

Never trust, authorize - at every request

The crux of a Zero Trust approach to authorization is continuous, contextual verification. Rather than relying on a user’s initial login and then assuming everything they do for the next 30 minutes is kosher, we treat each action as needing its own check. As one government zero-trust memo put it, the system should “check access permissions at every attempt of access,” moving beyond static one-time role checks to dynamic attribute-based decisions. In practice, this means whenever Service A calls Service B, or whenever User X tries to perform Action Y on Resource Z, we evaluate whether that should be allowed right now, given all relevant context (identity, role, resource, environment, etc.).

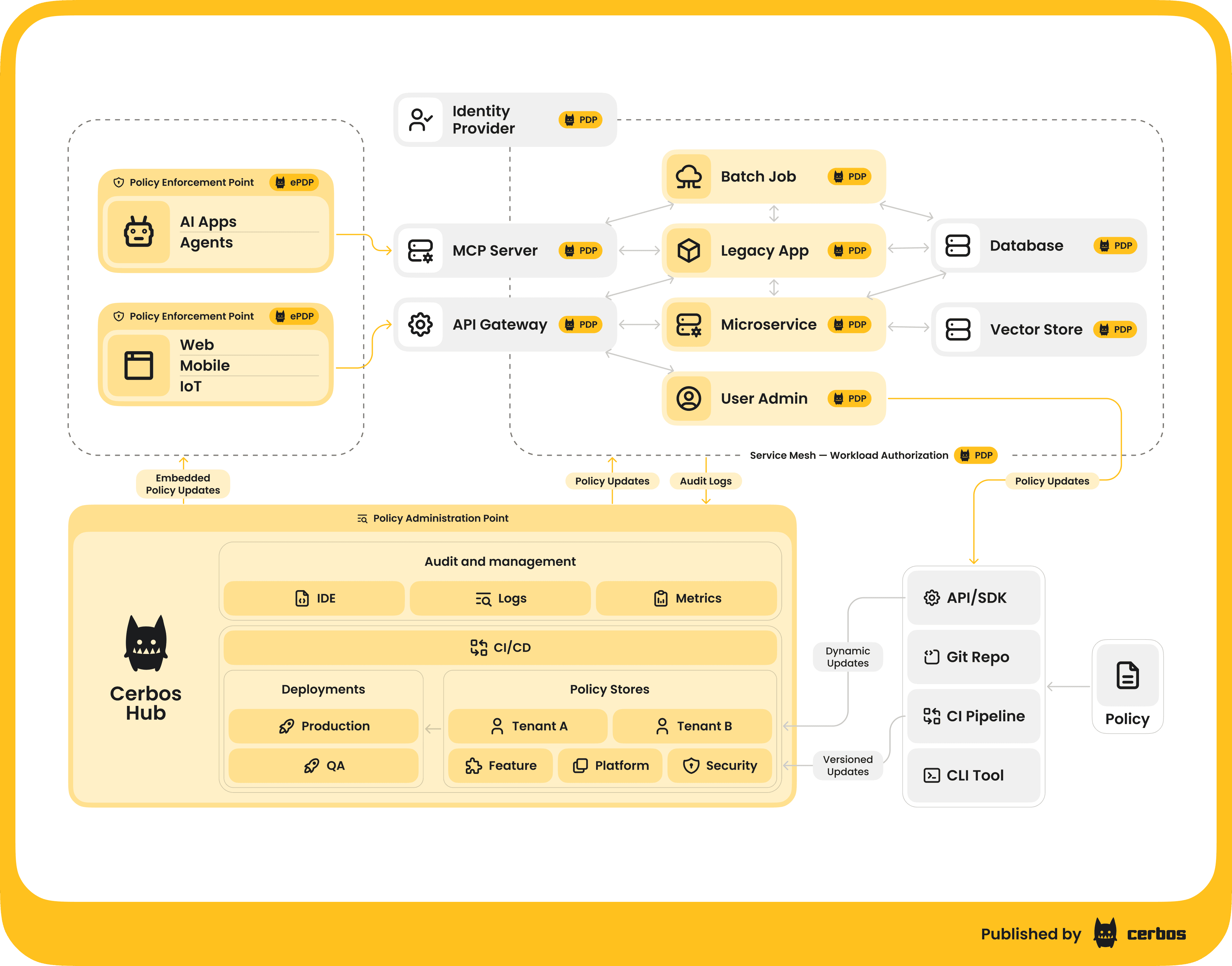

This might sound like a lot of work, and it is, if you try to implement it manually everywhere. But this is where tooling and modern architecture patterns come to the rescue. Alex described a pattern of externalizing authorization into a dedicated service or component, often called a Policy Decision Point. Instead of hard-coding all those rules in each application, you define them in policies and use a common engine to evaluate access requests. Solutions like Cerbos are examples of PDP engines designed for this purpose.

This approach turns spaghetti code from the previous code example into something simple:

Here’s how it works conceptually

Whenever your application needs to make an authorization decision, it formulates a question to the PDP. The question typically includes who (the authenticated user or service, often called the principal), what action they are trying to do (e.g. “delete record”), and on what resource (e.g. “record #12345 in the orders database”).

The PDP evaluates this against policies that you’ve written, essentially your “standard operating procedures” for access, and replies with allow or deny. Potentially with additional info like reasons or context. The application, sometimes called the Policy Enforcement Point, then allows or blocks the action based on that decision.

The beauty of this approach is that your authorization logic becomes centralized, standardized, and easier to manage. You can update a policy in one place, and all services will enforce the new rule - no need to hunt down and modify dozens of microservices. Policies are written in a declarative way, for example, using YAML or a purpose-built policy language, that is easier to read and audit than scattered if/else statements in code. They can also be version-controlled, tested, and even analyzed independently of your application code. And since the PDP generates a decision for each request, it can also produce a consistent audit log of those decisions across your system (who tried to do what, allowed or denied, and under which policy version) - a lifesaver for compliance and debugging.

Alex likened having a clear authorization policy to having a well-defined checklist or procedure in aviation. Just as pilots rely on standard checklists, instead of ad-hoc judgment, to handle emergencies, engineers can rely on explicit policies to handle access control. Writing down the rules in a policy file might feel like extra upfront work, but it creates a single source of truth that everyone including developers, SREs, auditors, even product managers, can discuss and agree on. It moves the conversation from “scattered code says X” to “our policy says X”.

Implementing policy based authorization

How would you implement this in practice? One way is to deploy a PDP as a service that all your apps query. For example, Cerbos can run as a sidecar next to your application container or as a centralized service. Your code, upon each protected operation, makes a call like “Hey Authorization Service, should user alice be allowed to UPDATE invoice#456?” The PDP then checks the relevant policy (perhaps something like: “Managers can update invoices in their department; regular employees can only view them; invoices marked finalized cannot be edited,” etc.) and returns a decision. This call typically adds some latency, but a well-engineered PDP is highly optimized and can often respond in microseconds or a few milliseconds - plus, running it as a local sidecar or library can minimize network overhead. Modern orchestration makes it feasible to co-locate these decision engines close to your app, so you don’t have to worry about a huge performance penalty in exchange for security.

Notably, Google’s implementation of Zero Trust, BeyondCorp, was built around the idea that every internal application should be treated as if it’s exposed to the open internet. That means every request to every service is authenticated and authorized as if coming from an untrusted network - no assumptions that “it’s an internal call, so it’s fine.” Using an identity-aware proxy and per-request policy checks, Google proved that you can ditch the traditional VPN model and still stay secure. This is exactly the philosophy we can all adopt: strong authentication and fine-grained authorization everywhere, so even if one part of the system is compromised, an attacker can’t move laterally to the crown jewels.

Of course, externalizing authorization into a service comes with considerations. It’s a new component to deploy and maintain, and you’ll need to learn how to write policies effectively. But the benefits are significant: you get consistency across your stack, the flexibility to change rules without code changes, and the ability to enforce the principle of least privilege rigorously. By decoupling business authorization logic from application code, developers can focus on core features while security teams get a clear handle on access control rules. It’s a classic win-win in large organizations - and even smaller teams benefit by avoiding costly security oversights.

For a deep dive into implementing externalized authorization, check out our 80+ page ebook on the topic. It provides practical steps to follow for this architectural change, from foundational planning to Proof of Concept rollout and establishing governance.

Stronger security through layered trust

Layering your security defenses, like layers of Swiss cheese, dramatically lowers the risk that any single failure will lead to a breach. A firewall might block 99% of threats, but you have identity checks and encryption to catch those that sneak past. Your authentication system might verify users initially, but fine-grained authorization on each action will stop a rogue insider or compromised account from doing damage. And even if something does slip through all these controls, monitoring and alerts ensure you can react quickly to minimize impact. This is the essence of a robust Zero Trust architecture: verify everything, trust nothing by default.

Authorization, in particular, has emerged as the linchpin for enforcing zero trust at the application level. By never skipping the “Can Alice do this right now?” question, you close the gap that many attackers have exploited in the past. And thanks to modern, developer-friendly solutions, implementing this doesn’t have to be painful or intrusive to your workflow. In fact, it can save time in the long run - think of all the custom ad-hoc permission code you don’t have to write, and all the future security bugs you’ll avoid.

In Alex’s talk, he joked that in a truly secure setup, you could theoretically put each of your microservices directly on the internet and still be safe, because every single request would be properly authenticated and authorized, no matter where it comes from. While you might not literally expose all your internal APIs, having that mindset means you’ve achieved a deep level of trust in your security layers. Every slice of cheese is doing its job.

At the end of the day, layering is about resilience. Complex systems will always have flaws (holes), but if we design thoughtful, independent layers of defense, we can prevent a small flaw from becoming a major breach. Aviation learned this through hard lessons and now enjoys an incredible safety record. In cybersecurity, we’re on a similar journey, and embracing layered security with Zero Trust and strong authorization is how we get there.

TL;DR:

By taking inspiration from aviation safety and modern Zero Trust principles, we can build systems that are not only more secure, but also more adaptable. The next time you’re designing an application’s security, think about the Swiss Cheese model: what layers can you add so that even if one layer has a hole, the next layer will catch the issue? This mindset, combined with the right tools for things like dynamic authorization, will go a long way toward keeping your software and data safe in an increasingly hostile digital world.

If implementing authorization sounds daunting, it doesn’t have to be. Cerbos was designed to provide that missing layer of contextual, policy based access control without a huge engineering lift. You can check Cerbos out here or book a quick call with a Cerbos engineer to see how it could fit into your stack.

FAQ

Book a free Policy Workshop to discuss your requirements and get your first policy written by the Cerbos team

Recommended content

Mapping business requirements to authorization policy

eBook: Zero Trust for AI, securing MCP servers

Experiment, learn, and prototype with Cerbos Playground

eBook: How to adopt externalized authorization

Framework for evaluating authorization providers and solutions

Staying compliant – What you need to know

Subscribe to our newsletter

Join thousands of developers | Features and updates | 1x per month | No spam, just goodies.

Authorization for AI systems

By industry

By business requirement

Useful links

What is Cerbos?

Cerbos is an end-to-end enterprise authorization software for Zero Trust environments and AI-powered systems. It enforces fine-grained, contextual, and continuous authorization across apps, APIs, AI agents, MCP servers, services, and workloads.

Cerbos consists of an open-source Policy Decision Point, Enforcement Point integrations, and a centrally managed Policy Administration Plane (Cerbos Hub) that coordinates unified policy-based authorization across your architecture. Enforce least privilege & maintain full visibility into access decisions with Cerbos authorization.